An outbreak of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in chicken and turkey flocks has spread across 24 U.S. states since it was first detected in Indiana on February 8, 2022. Better known as bird flu, avian influenza is a family of highly contagious viruses that are not harmful to wild birds that transmit it, but are deadly to domesticated birds. As of early April, the outbreak had caused the culling of some 23 million birds from Maine to Wyoming. Yuko Sato, an associate professor of veterinary medicine who works with poultry producers, explains why so many birds are getting sick and whether the outbreak threatens human health.

Why is avian influenza so deadly for domesticated birds but not for wild birds that carry it?

Avian influenza (AI) is a contagious virus that affects all birds. There are two groups of AI viruses that cause disease in chickens: highly pathogenic AI and low pathogenic AI.

HPAI viruses cause high mortality in poultry, and occasionally in some wild birds. LPAI can cause mild to moderate disease in poultry, and usually little to no clinical signs of illness in wild birds.

The primary natural hosts and reservoir of AI viruses are wild waterfowl, such as ducks and geese. This means that the virus is well adapted to them, and these birds do not typically get sick when they are infected with it. But when domesticated poultry, such as chickens and turkeys, come in direct or indirect contact with feces of infected wild birds, they become infected and start to show symptoms, such as depression, coughing and sneezing and sudden death.

There are multiple strains of avian influenza. What type is this outbreak, and is it dangerous to humans?

The virus of concern in this outbreak is a Eurasian H5N1 HPAI virus that causes high mortality and severe clinical signs in domesticated poultry. Scientists who monitor wild bird flocks have also detected a reassortant virus that contains genes from both the Eurasian H5 and low pathogenic North American viruses. This happens when multiple strains of the virus circulating in the bird population exchange genes to create a new strain of the virus, much as new strains of COVID-19 like omicron and delta have emerged during the ongoing pandemic.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk to public health from this outbreak is low. No human illnesses have been associated with this virus in North America. That was also true of the last H5N1 outbreak in the U.S. in 2014 and 2015.

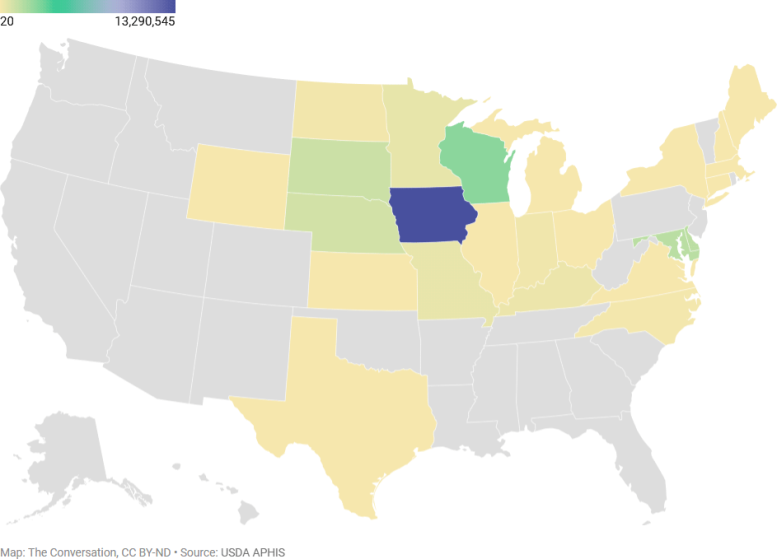

Avian influenza has been detected in at least 24 states

Approximately 23 million chickens, turkeys, and game birds in commercial and backyard flocks had been culled as of April 3, 2022, after bird flu was detected on their sites.

Should people avoid poultry products until this outbreak ends?

No, that’s not necessary. Infected poultry or eggs do not enter the food supply chain.

To detect AI, the U.S. Department of Agriculture oversees routine testing of flocks done by farmers and carries out federal inspection programs to ensure that eggs and birds are safe and free of virus. When H5N1 is diagnosed on a farm or in a backyard flock, state and federal officials will quarantine the site and cull and dispose of all the birds in the infected flock. Then the site is decontaminated.

After several weeks without new virus detections, the area is required to test negative in order to be deemed free of infection. We call this process the four D’s of outbreak control: diagnosis, depopulation, disposal, and decontamination.

Avian influenza is not transmissible by eating properly prepared and cooked poultry, so eggs and poultry are safe to eat. The USDA recommends cooking eggs and poultry to an internal temperature of 165 degrees Fahrenheit (74 Celsius).

Are avian influenza outbreaks happening more frequently around the world, or do we just hear more about them than we did 20 or 30 years ago?

The dynamics of the spread of avian influenza viruses are very complex. HPAI is a transboundary disease, which means it is highly contagious and spreads rapidly across national borders.

Some research indicates that detection of HPAI viruses in wild birds has become more common. Reports are seasonal, with a peak in February and a low point in September. There are ongoing outbreaks of HPAI in wild birds in Asia, Europe and Africa. Many migratory bird species travel thousands of miles between continents, posing a continuing risk of AI virus transmission.

In addition, we have better diagnostic tests for much more rapid and improved detection of avian influenza compared to 20 to 30 years ago, using molecular diagnostics such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests – the same method labs use to detect COVID-19 infections.

Farmers can take steps to make their flock more biosecure, such as preventing birds and their feed from being exposed to wild birds.

What’s the prospect of developing a vaccine for poultry that could reduce the economic harm from outbreaks?

Many factors would have to be weighed before adopting vaccination as a strategy for controlling HPAI. At this time, the Department of Agriculture has not approved the use of vaccination in the U.S. for protecting birds from avian influenza.

One reason for this is that using vaccines would potentially affect international trade and poultry exports. Importers would not be able to distinguish vaccinated birds from infected birds based on the routine testing, so they might ban all U.S. poultry exports.

Vaccination also could delay outbreak detection, since it can potentially hide non-apparent infections in infected birds. And if infections go unnoticed, they could spread to other farms before farmers can put control measures in place.

Avian influenza vaccines can reduce clinical signs, sickness and death rates in domestic poultry, but they would not prevent birds from becoming infected with the virus. Ultimately, the USDA’s goal is to eradicate HPAI quickly after it is detected. However, vaccines could be used to help control an outbreak, and this is an option that the agency is investigating now.

Written by Yuko Sato, Associate Professor of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University.

This article was first published in The Conversation.![]()