New ATLAS and CMS analyses place tight limits on the strength of the Higgs boson’s interaction with the charm quark.

Since the discovery of the Higgs boson a decade ago, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have been hard at work trying to unlock the secrets of this special particle. In particular, they have been investigating in detail how the Higgs boson interacts with fundamental particles such as those that make up matter, that is, quarks and leptons. In the Standard Model of particle physics, these matter particles fall into three categories, or “generations”, of increasing mass, and the Higgs boson interacts with them with a strength that is proportional to their mass. Any deviation from this behavior would provide a clear indication of new phenomena.

ATLAS and CMS have previously observed the interactions of the Higgs boson with the heaviest quarks and leptons, i.e. those of the third generation, which agree with the predictions from the Standard Model within the current measurement precision. They have also obtained the first indications that the Higgs boson interacts with a muon, a lepton of the second generation. However, they have yet to observe it interacting with second-generation quarks. In two recent publications, ATLAS and CMS report analyses that place tight limits on the strength of the Higgs boson’s interaction with a charm quark, a second-generation quark.

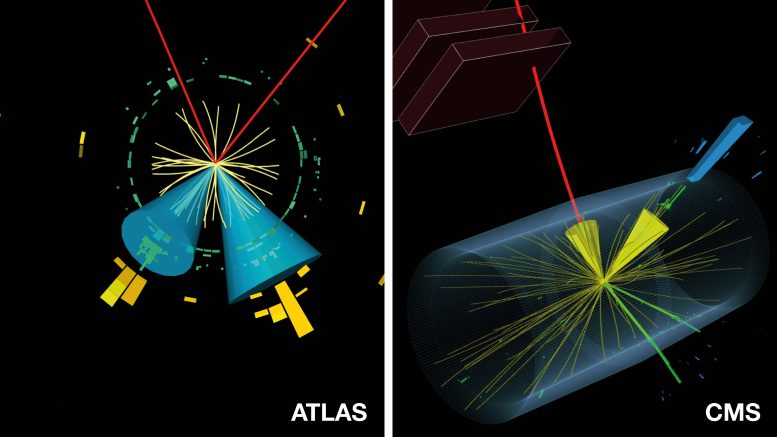

Candidate events for a Higgs boson produced in association with a Z boson, as recorded by ATLAS (left) and CMS (right). The Higgs boson decays into a pair of jets (cones) originating from charm quarks, and the Z boson decays into muons (red lines on the left) or electrons (green lines on the right). Credit: CERN

ATLAS and CMS study the Higgs boson’s interactions by looking at how it transforms, or “decays”, into lighter particles or how it is produced together with other particles. In their latest studies, using data from the second run of the LHC, the two teams searched for the decay of the Higgs boson into a charm quark and its antimatter counterpart, the charm antiquark.

In the Standard Model, this decay is relatively rare, occurring only 3% of the time. What’s more, the decay is extremely hard to spot because the two sprays, or “jets”, of particles that it generates can also be produced by other processes at far higher rates. To more easily identify this decay, ATLAS and CMS targeted their searches at Higgs bosons produced together with a W or a Z boson decaying to electrons, muons (W, Z) or neutrinos (Z), and they used sophisticated machine-learning techniques to identify jets originating from charm quarks. CMS also looked for high-momentum, or “boosted”, Higgs bosons that result in two charm jets collapsing into a wide jet.

The teams found no significant indication of the decay of the Higgs boson into charm quarks in the data, but their analyses set bounds on the rate at which this decay should occur when the Higgs boson is produced along with a W and Z boson. These bounds correspond to upper limits on the interaction strength of the Higgs boson with a charm quark, of 8.5 and 5.5 times the Standard Model prediction in the case of ATLAS and CMS, respectively.

The ATLAS team went on to combine their analysis with a measurement of the Higgs boson decay into beauty quarks, demonstrating that the Higgs boson interacts more weakly with the charm quark than it does with the beauty quark. In other words, they found that the Higgs boson interacts differently with quarks of the second and third generations, as predicted by the Standard Model.

Interestingly, the CMS study allowed the CMS researchers to observe for the first time at a hadron collider the decay of the Z boson into charm quarks, a bonus observation that resulted from a validation step in their search for the decay of the Higgs boson into charm quarks.